In Praise of Breakup Songs

& other testaments to the transformative power of past love

Hi friends,

I’ve been sitting on this blog for a WHILE. First, I was tinkering with it while I was busy writing for the Culture & Criticism desk at BuzzFeed News. Then, Substack deleted my whole newsletter (long story, text/DM me if you want the details of my feud), and I have only just gotten it back up and running. But I really am thrilled to be working on the fixate again, and I have some big plans: 1) a recommendation column called Old/New/Offline, where I recommend 3 old, 3 new, and 3 offline experiences of art & culture worth checking out, and 2) a collaborative print version of “Songs from College” aka SfC: the zine!

Anyway, this is going to be a long one, so I should get into it. But first, a quick recap, in case you missed the work I was doing at BuzzFeed News: I published my first longform reported feature about the sex lives of Gen Z, plus I wrote about learning to run and learning to write, Brooke Shields and the perils of beauty, The Power and amorality, Beyoncé and Bad Bunny, nepo babies, SZA supremacy, The Sex Lives of College Girls, and, infamously, the Mindy Kaling backlash. I learned a ton, and I adored my team. My editors and coworkers were all incredibly generous in helping me grow as a writer, and I will always be grateful for their unfailing support. But more on that later.

Today, I’m here to write about love and music.

In February, the Paris Review ran a series of mini essays on “love songs, broadly defined.” The first one I found is also my favorite — Elena Saavedra Buckley’s tribute to “I Want To Be Your Man” by Roger Troutman. It’s about moving to LA after a breakup, and it contains these two devastating sentences:

I’ve been thinking about breakups — and breakup songs — ever since.

Recently, I rediscovered an all-time great breakup song: Jhene Aiko’s “None of Your Concern,” feat. Big Sean, from her 2020 album Chilombo. It’s a little non-traditional — it’s not so much a post-breakup song as a mid-breakup song, in which Aiko ruminates on her relationship problems before ultimately committing to a split. In the first verse, she’s still wondering, “Isn’t this worth saving?” By the last, she spits, “Get your bitch ass off of my phone.”

It’s the chorus that really gets me. In her verses, Aiko ranges from bitter to disappointed to dramatic. She complains that they “should have never dated,” snaps at her boyfriend’s “audacity to question me,” and remembers how he made her feel “traumatized and suicidal / sick and tired.” The verses contain all the venom she wants to spew at him, all the angry arguments they’ve had over months of discontent. But the chorus is so simple as to be resigned: Weary from fighting, Aiko sighs, “It’s none of your concern anymore.”

This is the song’s radical insight, its gut punch, its punctum. What this moment understands so keenly is that the worst part of any breakup — platonic, romantic, whatever — manifests in moments that are basically unremarkable. The screaming, crying, and fighting don’t hurt as much as looking up one day, ready to say to someone, “Here’s this thing that made me think of you,” but then realizing they aren’t there; the bottom has fallen out, and there’s no one to say that to. Only in that absence, mundane as it is, can we glimpse the need that has calcified within us for another person, the completeness with which we were once intertwined such that otherwise ordinary moments in the day — when the idlest of our thoughts come to the surface — once belonged to them too. That’s sacred. That’s something only God can otherwise do: witness and participate in our solitude.

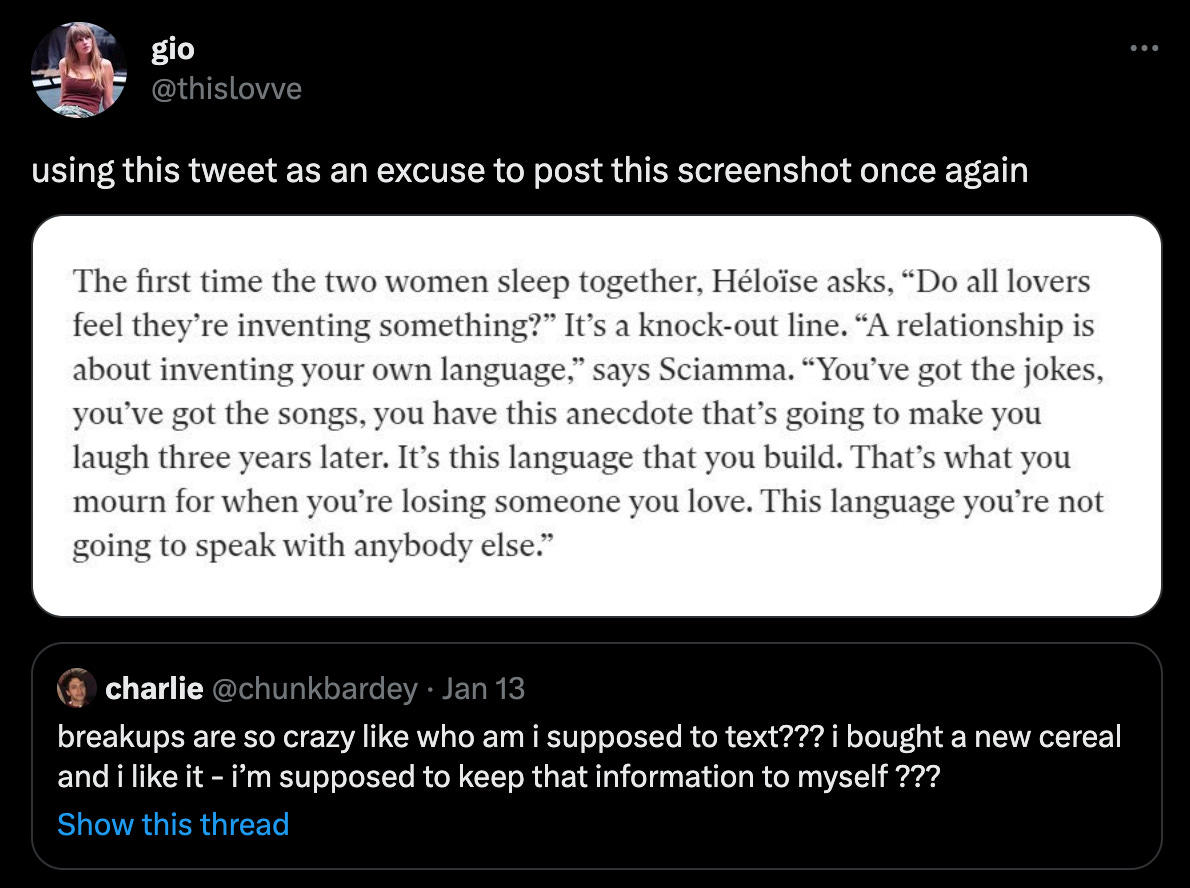

Here are two more ways to say this, courtesy of Twitter:

I love a song about falling in love as much as anyone else does, but I’ve become less and less interested in love as a giddy possibility. It’s easy to gossip endlessly about friend crushes and honeymoon phases, first dates and flirtations. It’s easy to romanticize strangers, to stash them high in the glossy, frictionless realm of fantasy. It’s a mode of thinking that both stems from and engenders art in which the Epic Love Story is one where nothing ever really happens, where the back-and-forth, will they–won’t they dynamic governs the entire relationship. That narrative of love dominates our most popular stories, as in the relentlessly annoying Daisy Jones & The Six, where the central love story is a decadeslong unconsummated vibe between a married man and a blank personality of a woman. (At least in the show. I haven’t read the book, and you can’t make me.) Billy and Daisy talk a lot about how they understand each other’s rich inner lives the way no one else can, but all they do is mope about how they can’t be together, which, sorry, does not make them soulmates.

For the New York Review of Books, Lorrie Moore diagnosed the romanticization of evasion and miscommunication as a Millennial problem, epitomized by Sally Rooney’s Normal People. Every turn of the book’s plot hinges on Marianne and Connell abandoning each other based on “the flimsiest misunderstandings,” until the fateful force of their connection inevitably reunites them. In such a story, love is no stronger than destiny; circumstances out of the characters’ control drive them apart and back together. Love is innate mutual gravity, unchangeable by choice or action. Love is permanently suspended in a mode of possibility. At the end of Normal People, as in Daisy Jones, the future of the characters remains unclear; Connell and Marianne are about to live on separate continents for the first time, while Billy is about to ask Daisy out on a real date for the first time. The enticing question is: Will they be able to make their love work once they give it a real shot? The convenient answer is: You’ll never know.

I’m no longer interested in love stories that flinch away from commitment. I feel far more in awe of how love transforms us through sustained risk and the choice to show up for one another, how it deepens through forces as boring as inertia and proximity. How intimate it is to lie in your best friend’s bed while you’re both on your phones, something I used to regard as a waste of time, but which now strikes me as miraculous in the way it reveals comfort and closeness that cannot be bought, faked, or chalked up to fate. It can only be earned, accumulated as though by accident over vast reserves of time. I’m more in awe of love that’s like a half-forgotten history, a smudgy, overstamped checkout card in the back of a library book: Who has borrowed from me? Who have I lent myself to?

This retrospective view of love feels more capacious than one fixated on the future. It puts family and friendship on an equal playing field alongside romance, and it resists the tendency to talk about romance as though fantasy is worthier than reality. Instead, it valorizes the importance of what we have already shared with the people who have made us what we are. And it offers a healthier alternative to thinking about breakups; it’s so easy to be embarrassed of our past relationships, once we slough them off, but it seems kinder to ourselves to admit that they were truly formative, that we needed our exes for as long as we did.

“None of Your Concern” is a phenomenal breakup song, a thrilling embodiment of a very specific mood. Its mournful piano and muffled percussion melt together underneath Jhené Aiko’s effortlessly smoky voice, letting all the inflections of her grief ring out raw and clear: vivid bitterness, nursed hurt, the indignation of self-preservation. It’s so mellow, so easy to dwell in, that eventually it starts to sound less like a breakup song than a love song, full stop. It’s not a rejection of love, but a celebration of its abundance. It inhabits the eroded huecos of a broken heart. It offers evidence of a past relationship’s history and heft, made visible in the space it has left. That, I think, is more intimate than any imagined future romance, any hope for redemption that we place in passing strangers.

P.S. I thought of a lot of other breakup songs I wanted to include in this blog, from the Vaccines’ optimistic “If You Wanna,” a refreshingly energetic embrace of the possibility of getting back together, to Julia Jacklin’s “End of A Friendship,” which I’ve started to treat as the soundtrack to the novel I’m working on, to Ariana Grande’s “thank u, next,” which is the most basic song I truly love. I even wanted to tell the story of the time I drove from Tahoe to LA during a 103-degree heat wave, unexpectedly crying on Highway 99 to the deliciously glitchy voices of Idina Menzel and Kristin Chenoweth, the human wounds opening in their throats as they sang those essential lyrics from Wicked’s “For Good:” “Who can say if I’ve been changed for the better? / Because I knew you, I have been changed / For good.” It’s a perfect lyric to capture all I’ve wanted to say here.

But then recently my sweet friend Cody sent a song in the BuzzFeed News #music-fridays Slack channel, one to capture post-layoff grief: “Expert in a Dying Field” by the Beths. The Beths are one of my favorite bands I’ve found recently, in part because of lead singer Elizabeth Stokes’ delightful New Zealand accent (If you were an “aur naur, Cle-aur” person, you’ll love the song “Knees Deep,” which features the unbeatable opening: “Watching light through water / I wanna bi-yund the way it bi-yunds”). But I hadn’t listened to this track yet, and I’m so glad Cody sent it now. The song likens a breakup to, well, being an expert in a dying field: having all this hard-earned industry knowledge that you no longer know what to do with. It’s a thrilling analogy, one made all the more poignant by the way it boomerangs back around to reflect the lostness and dissonance of people who want to give their lives to a shrinking industry, writers and editors and thinkers who have a lot of ideas and vanishingly few places in which to bring those ideas to life.

In the spirit of love as record of the people who have helped you grow, I’m deeply, deeply grateful to the people I met during my brief little stint at BuzzFeed News: Tomi, my genius editor & mentor; Estelle, Scaachi, Venessa, Albert, Alessa, Elamin, & Steph, who all welcomed me so warmly to the team & showered me with support; Anthony, Mos, & Fjolla, my endlessly encouraging fellow fellows; Kelsey, Steffi, Maddie, Lil, Emerson, Cody, Zia, Jamilah, Karolina, Jason, Ken; all the people who made time to reach out to me individually & connect all across the country. It was truly so much fun to get a glimpse at the whole ecosystem that made BFN tick, from the copy desk to the audience team to art to the union (thank you for my severance package oh my god). I was not there for very long, but it really was a tremendous newsroom, one with a vibrant & hilarious history best told by the people who lived through years of it.

To everyone at BFN, thank you for everything! Cheers & tears to moving on.